10 must know fact About Breast cancer pathophysiology and Investigation – From Life-Saving Knowledge to Dangerous Misses

Breast Cancer Pathophysiology and Investigation of Breast Disease:

Introduction:

Patients with breast problems make up 15–20% of new referrals to general surgical outpatient clinics. Virtually every woman with a breast lump, breast pain, or discharge from the nipple fears that she has cancer.

The anxiety that results is made up of three components:

- Unknown course

- Threat of mutilation

- Fear of dying

Previously, this often prevented women from seeking early medical advice. But in recent years, public awareness and screening and the possible advantage of early treatment have encouraged earlier presentation.

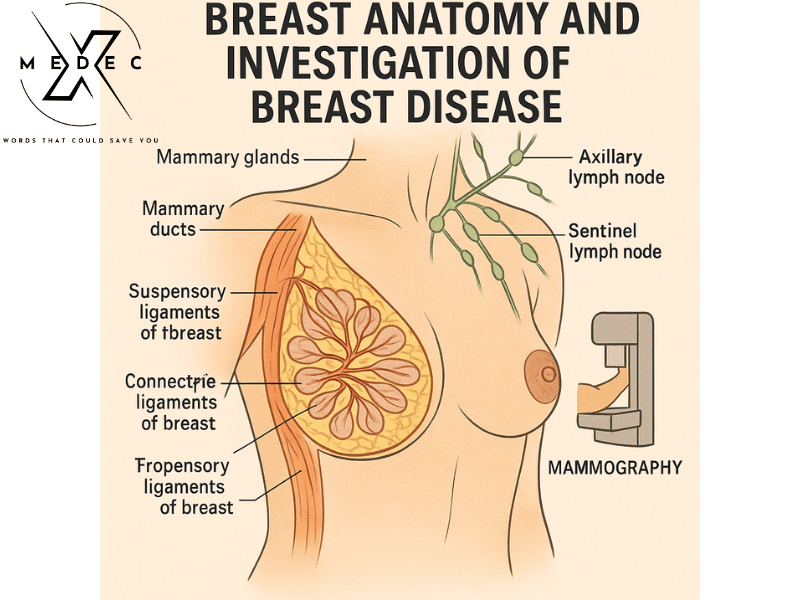

Anatomy:

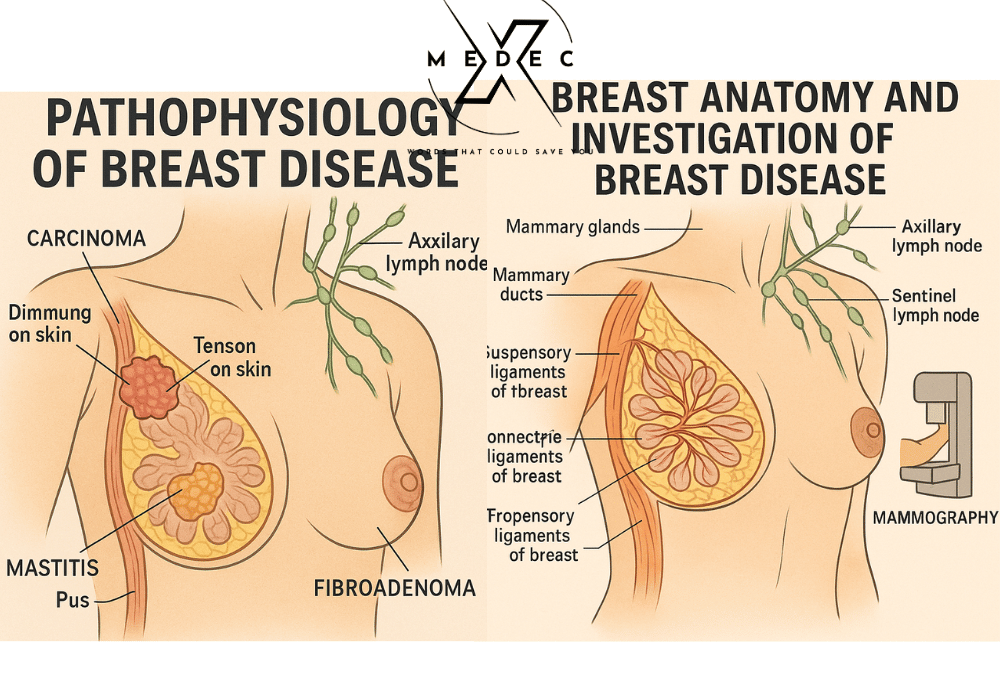

The mammary glands are modified sweat glands in the superficial fascia anterior to the pectoral muscle. The breast lies between the skin and the pectoral fascia, to which it is loosely attached.

It extends from the clavicle superiorly down onto the abdominal wall, where it extends over the rectus abdominis, external oblique, and serratus anterior muscles.

The axillary tail of the breast runs between the pectoral and latissimus dorsi muscles to blend with the fat. A layer of loose connective tissue separates the breast from the deep fascia over the pectoralis muscle and provides some degree of movement.

The breast extends vertically from rib II to VI and transversely from the sternum to as far laterally as the mid-axillary line.

In certain areas of the breast, the connective tissue stroma condenses to form well-defined ligaments, the suspensory ligaments of the breast, which are continuous with the dermis of the skin and support the breast.

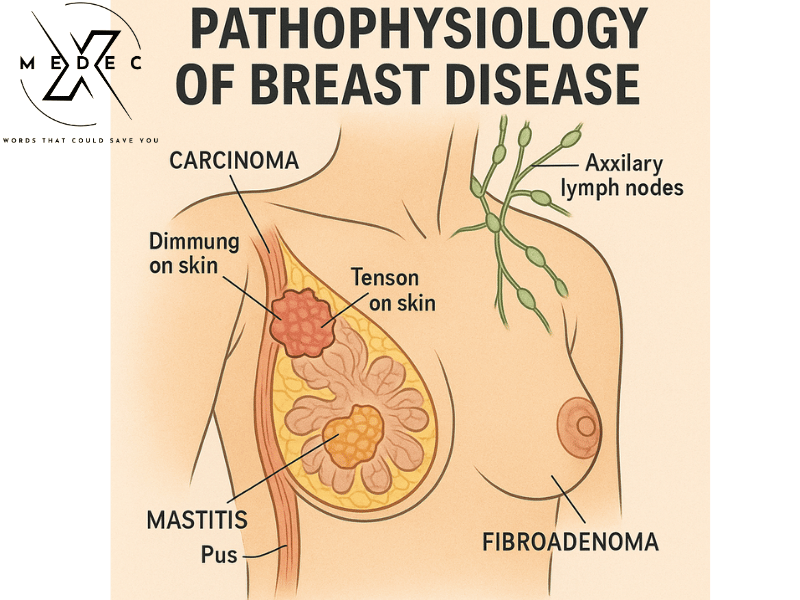

Carcinoma of the breast creates tension on these ligaments, causing pitting of the skin.

The mammary glands consist of a series of ducts and associated secretory lobules. These converge to form 15 to 20 lactiferous ducts which open independently onto the nipple.

The nipple is surrounded by a circular pigmented area of skin termed the areola.

Arterial Supply:

The vascular supply and drainage can occur by multiple routes.

Laterally, vessels arise from the axillary artery—superior thoracic, thoracoacromial, lateral thoracic, and subscapular arteries.

Medially, branches come from the internal thoracic artery.

The second to fourth intercostal arteries also supply the breast via branches that perforate the thoracic wall and overlying muscle.

Lymphatic Drainage:

Lymphatics of the breast drain predominantly into the axillary and internal mammary lymph nodes. Axillary nodes receive approximately 85% of the drainage.

The axillary nodes are arranged in three levels by their relation to the pectoralis minor muscle:

- Nodes lateral to the pectoralis minor are considered Level I.

- Nodes beneath the pectoralis minor are classified as Level II.

- Nodes medial to the pectoralis minor are Level III.

Anatomically, axillary lymph nodes are divided into:

- Anterior group – along the lateral thoracic vessels

- Posterior group – along the subscapular vessels

- Lateral group – along the axillary vein

- Central group – embedded in the fat of the axilla

- Apical group – receives efferents from all other groups

- Interpectoral nodes

(The first draining lymph node is called the sentinel lymph node)

Breast cancer Pathophysiology

Congenital Abnormalities:

These are most commonly the result of persistent extra-mammary portions of the breast ridge.

In the 6th week of embryonal development, a bilateral ridge called the milk line develops and extends from the axilla to the groin.

Segments coalesce into nests of cells and in humans, all but one of these nests (opposite the fifth intercostal space) disappear.

In 1–5% of people, one or more of these persist as supernumerary or accessory nipples.

Less frequently, accessory breasts may develop. The common site for an accessory nipple is between the normal breast and the umbilicus along the milk line.

The most common site for an accessory breast is the lower axilla.

Some degree of breast asymmetry is normal, with the left usually being larger than the right. One breast can also be absent or hypoplastic.

Investigation of Breast Disease:

Approximately 25% of all surgical referrals relate to breast problems.

In the UK, one in four women will attend a breast clinic and one in ten will develop breast cancer at some point in their lives.

Thorough history taking and good clinical examination can lead to a clinical diagnosis, which needs to be confirmed or other possibilities excluded.

Commonly Done Investigations:

Mammography:

Soft tissue radiographs are taken by placing the breast in direct contact with ultrasensitive film and exposing it to low voltage, high amperage X-rays.

This requires compression of the breast between two plates and is uncomfortable.

The radiation dose is kept as low as possible (0.5–1.5 mGy/film).

A single oblique view or two views (an oblique and a craniocaudal) can be obtained.

Mammography allows the detection of mass lesions, areas of parenchymal distortion, and microcalcification.

Because breast tissue is relatively radiodense in women under 35 years of age, mammography is rarely of value in this group. It is done only in selected cases in our country.

Ultrasonography:

Ultrasound is particularly useful in young women with dense breasts.

It helps distinguish between cystic and solid lesions and can localize impalpable areas of pathology.

✅ [Guideline Note – Bangladesh]: In most hospitals across Bangladesh, ultrasound is the first-line investigation for palpable breast lumps in women under 35.

However, it is not suitable as a standalone screening tool and remains operator dependent.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI is a highly sensitive imaging tool for both invasive and non-invasive breast cancer.

It is especially useful for:

- Evaluating suspected recurrence post breast-conserving surgery

- Assessing implant rupture or leakage

- Screening in high-risk patients (e.g., BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations)

✅ [Guideline Note – International]: According to the American Cancer Society, MRI is recommended as a supplemental screening tool in high-risk women but not for average-risk populations.

✅ [Bangladesh Context]: Due to high cost and limited availability, MRI is not commonly used in most centers unless specifically indicated.

Needle Biopsy / FNAC:

FNAC is a minimally invasive technique for obtaining cells from a breast lump, typically using a 21G or 23G needle.

It’s useful for quick cytological diagnosis and is often performed under local anesthesia.

✅ [Updated Practice]:

- Core Needle Biopsy (CNB) is now the preferred method for tissue diagnosis as it preserves histological architecture, allowing better distinction between in situ and invasive disease.

- FNAC is still used widely in Bangladesh, especially in primary care and government hospitals due to ease, low cost, and quick results.

Open Biopsy:

Should only be performed after imaging and FNAC/needle biopsy.

It is considered when:

- FNAC/core biopsy is inconclusive

- There’s a suspicion of malignancy that hasn’t been confirmed

- There is a need for excisional biopsy

✅ [Guideline Note – International]: Open biopsy is less favored now due to the risk of unnecessary surgery and cosmetic concerns unless absolutely indicated.

Frozen Section:

The routine use of frozen section for breast cancer diagnosis is no longer recommended.

It has limited sensitivity (~80%) for lymph node metastasis.

✅ [Bangladesh Practice]: Still performed in many hospitals for suspicious lumps, especially where rapid diagnosis is needed before definitive surgery.

Triple Assessment:

Triple assessment involves:

- Clinical Examination

- Imaging (Ultrasound/Mammography)

- Tissue Sampling (FNAC or Core Biopsy)

The combination has a positive predictive value over 99.9%, making it the gold standard approach in breast lump evaluation.

✅ [WHO Recommendation]: This approach is internationally accepted and forms the basis of Breast Cancer Early Detection Programs.

Benign Breast Disease (ANDI Classification):

Includes:

- Cyclical nodularity

- Mastalgia

- Cysts

- Fibroadenomas

Also includes:

- Duct ectasia / Periductal mastitis

- Pregnancy-related lesions: Galactocele, lactational abscess

- Congenital disorders: Inverted nipple, supernumerary breast

- Non-breast conditions: Tietze’s disease, sebaceous cysts

✅ [Bangladesh Context]: These conditions make up a significant portion of breast clinic cases, especially in young, reproductive-age women.

Fibroadenoma:

Benign encapsulated tumor made up of glandular and stromal tissue.

Common in women aged 15–30 years, often painless, mobile, and not attached to surrounding tissues.

✅ Diagnosis Tools:

- Clinical exam

- Ultrasound (hypoechoic, well-defined lesion)

- Mammography (in older women)

- FNAC or Core Biopsy (if diagnosis unclear)

✅ [Additional Point]:

- Fibroadenomas are not linked to cancer, though complex fibroadenomas may carry a slightly higher risk and require follow-up.

✅ [Bangladesh Note]: Most cases are managed conservatively unless the lesion is large, symptomatic, or increasing in size.

✅ Conclusion (Final Summary):

A careful clinical history and examination form the first steps of diagnosing breast disease.

Investigations like Ultrasound, FNAC/Core Biopsy, and Mammography/MRI help confirm the diagnosis.

Use of Triple Assessment ensures high diagnostic accuracy.

Benign conditions such as fibroadenoma or duct ectasia are common and can usually be managed non-surgically, especially in younger patients.

Breast pathophysiology and investigation ( Pathological Condition Investigation and Treatment)

Fibroadenoma – Malignancy Risk

Some malignant breast tumors can be mistaken for a fibroadenoma, so it is important for them to be diagnosed by a doctor.

On average, when the diagnostic pathway has been completed, about 5% may turn out to be malignant.

Treatment of Fibroadenoma

A fibroadenoma is a benign tumor, and sometimes surgery is not needed when the diagnosis is certain—especially in younger women.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, and particularly in older women, the tumor is generally surgically removed.

Larger fibroadenomas (usually >5–7 cm) are also typically removed.

No medications are used to treat fibroadenoma.

Phyllodes Tumor

Definition:

Phyllodes tumors (from Greek “phullon” meaning leaf), also called cystosarcoma phyllodes or phylloides tumors, are typically large, fast-growing masses that form from the periductal stroma of the breast.

They account for less than 1% of all breast neoplasms.

Presentation:

This is predominantly a tumor of adult women, most commonly occurring between the ages of 40 and 50, so before menopause.

Pathology:

Phyllodes tumors are fibroepithelial tumors composed of both epithelial and cellular stromal components.

They may be classified as benign, borderline, or malignant depending on histologic features such as:

- Stromal cellularity

- Infiltration at the tumor edge

- Mitotic activity

Treatment:

The standard treatment is wide local excision.

Most patients are cured with surgery.

The risk of local recurrence or metastasis is related to the tumor’s histologic grade.

Inflammatory Diseases of the Breast

Main types include:

- Abscess

- Fistula

- Duct ectasia (periductal mastitis)

- Fat necrosis

Breast Abscess

Abscess formation may occur:

- Within the breast tissue

- In the overlying skin (e.g., sebaceous cyst)

- In the inframammary fold

Definition:

An abscess is a localized collection of pus within a pyogenic membrane.

Symptoms:

- Pain

- Redness

- Swelling

Types:

- Lactational abscess: Occurs in young breastfeeding women, usually caused by Staphylococcus.

- Non-lactational abscess: Typically seen in middle-aged smokers, caused by Streptococci or anaerobic bacteria.

Periareolar abscess:

Occurs in women in their 30s due to active periductal inflammation (periductal mastitis).

It may progress to form a fistula.

Management:

- In early stages, antibiotics like Flucloxacillin, Augmentin, or Cephalexin (with anti-anaerobic and anti-staphylococcal properties) can prevent abscess formation.

- Once an abscess is formed, antibiotics are required for surrounding cellulitis.

- Pus is drained by repeated needle aspiration using a 19G needle or by formal incision and drainage under local or general anesthesia.

- A drain is not always needed.

- More than one drainage procedure may be required, especially if needle aspiration is used.

- Fistula formation is a possible complication.

- Adequate drainage is best achieved under general anesthesia.

Rare causes:

- Tuberculosis

- Actinomycosis

Inflammatory breast cancer must be excluded in patients with a solid inflammatory lesion or in abscesses not responding to appropriate treatment.

Fistula

A fistula between the epithelium of a breast duct and the skin may develop following an abscess.

The discharge site usually opens at the areolar margin.

Treatment:

Excision of the fistula through a circumareolar incision (including the involved duct up to the back of the nipple) under antibiotic cover is the treatment of choice.

Laying open the entire fistula tract is avoided due to the risk of scarring and breast deformity.

Duct Ectasia (Periductal Mastitis)

Duct ectasia is a dilatation of the breast ducts associated with periductal inflammation.

The pathogenesis is not uniform and may vary.

More common in smokers.

Pathogenesis (classic theory):

- Begins with dilatation of one or more major lactiferous ducts.

- Ducts fill with stagnant brown or green secretions.

- These secretions trigger an irritant reaction in surrounding tissues, leading to:

- Periductal mastitis

- Abscess

- Fistula formation

Sometimes a chronic indurated mass forms beneath the areola that mimics carcinoma.

Fibrosis may develop, causing slit-like nipple retraction.

Alternative theory:

Periductal inflammation is primary. Anaerobic bacteria may be involved.

Smoking association:

A strong link exists between smoking and recurrent periductal inflammation.

Some theories suggest arteriopathy as a contributing factor, while others propose that smoking enhances the virulence of commensal bacteria.

Smoking cessation significantly improves long-term outcomes.

Clinical Features (C/F):

The first noticeable symptom of breast pathology is typically a lump that feels different from the rest of the breast tissue.

Other signs may include:

- Changes in breast size or shape

- Skin dimpling

- Nipple inversion

- Spontaneous single-nipple discharge

Pain (mastodynia) is an unreliable indicator of breast disease but may point to other breast health issues.

Treatment:

In the case of a mass or nipple retraction, carcinoma must be excluded by obtaining a mammogram and cytology or histology.

If suspicion remains despite negative reports, the mass should be excised.

Antibiotic therapy may be attempted using Augmentin or Flucloxacillin combined with Metronidazole. However, surgery is often the only option that can provide a cure in these notoriously difficult conditions.

Definitive treatment may require Hadfield’s operation, which involves excision of all the major ducts.

Tuberculosis of the Breast:

Breast tuberculosis is rare and usually associated with active pulmonary tuberculosis or tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis.

It occurs more frequently in parous women (those who have given birth) and typically presents with:

- Multiple chronic abscesses

- Sinuses

- Bluish, thinned skin over the affected area

Diagnosis is made by bacteriological and histopathological examination.

Treatment is with anti-tuberculous chemotherapy. Healing is usually achieved, though it may be delayed.

Mastectomy should be reserved for cases with persistent residual infection.

Fat Necrosis:

Fat necrosis of the breast typically appears in postmenopausal women following breast trauma, such as a seatbelt injury.

It results in a localized inflammatory response.

It may be suspected based on clinical history but must be confirmed by triple assessment, as small cancers can mimic fat necrosis both clinically and radiologically.

Treatment: Reassurance is usually sufficient. However, if suspicion remains or if the patient requests it, an excisional biopsy may be performed.

Nipple Discharge – Common Causes:

Discharge from the surface:

- Paget’s disease

- Skin conditions (e.g., eczema, psoriasis)

- Rare causes (e.g., syphilitic chancre)

Discharge from a single duct:

- Bloody discharge:

- Intraductal carcinoma

- Intraductal papilloma

- Duct ectasia

- Serous discharge (any color):

- Fibrocystic disease

- Duct ectasia

- Carcinoma

Discharge from multiple ducts:

- Bloody:

- Carcinoma

- Duct ectasia

- Fibrocystic disease

- Grumous (thick/cheesy):

- Duct ectasia

- Purulent (pus-like):

- Infection

- Serous:

- Fibrocystic disease

- Duct ectasia

- Carcinoma

- Milky:

- Lactation

- Rare causes: Hypothyroidism, Pituitary tumor (prolactinoma)

Conclusion:

Sometimes inflammatory or infectious breast conditions may clinically mimic a neoplastic lesion (e.g., carcinoma).

Therefore, the principle of triple assessment (clinical examination, imaging, and histopathology) should be applied.

In select cases, frozen section during surgery may be useful to avoid repeated operations.

Carcinoma of the Breast

Introduction:

Breast carcinoma is the commonest cause of cancer-related death in middle-aged women in Western countries.

In England and Wales, 1 in 12 women will develop breast cancer.

Etiological (Risk) Factors:

- Geographical: Common in Western countries.

- Age: Extremely rare below 20 years of age.

- Gender: Less than 0.5% of cases occur in men.

- Genetic:

- Positive family history in a first-degree relative.

- Genetic mutations: BRCA1, BRCA2, TP53.

- Dietary:

- Diets rich in fat and alcohol.

- Low intake of phytoestrogens is associated with increased risk.

- Endocrine factors:

- Nulliparity (never having given birth)

- Not breastfeeding

- Late menopause

- Early menarche

- Use of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) — still under debate

Breast cancer Pathophysiology and Investigation – References

Mastodynia (Breast Pain)

• GP Journal – Mastalgia management

• Greater Manchester Cancer – Mastalgia Pathway

• MSD Manual – Mastalgia overview

Fibroadenoma

Phyllodes Tumor

• Medscape – Phyllodes Tumor overview

• BJS – Management of Phyllodes Tumors (OUP)

• WHO-classified Phyllodes Tumor (Wikipedia)

Breast Abscess / Mastitis

• Mayo Clinic – Mastitis/Abscess

• Medscape – Breast Abscess Management

Duct Ectasia (Periductal Mastitis)

Fat Necrosis

• Standard pathology references (e.g., Robbins & Cotran): mimic carcinoma; requires triple assessment.

Tuberculosis of the Breast

• Bangladesh NTP – TB Control Manual

• WHO – TB Guidelines

Nipple Discharge – Differential Diagnosis

• Mayo Clinic – Nipple Discharge Causes

• AAP – Common Breast Problems including discharge

Triple Assessment & Frozen Section

• NICE CG164: Suspected cancer – recognition and referral (Clinical guidelines support triple assessment)

• ASBS/National Comprehensive Cancer Network – uses triple assessment for diagnostic accuracy

Carcinoma of the Breast – Risk Factors & Epidemiology

• NCI – Breast cancer risk factors

• WHO – Breast Cancer Factsheet

Table of Contents Breast cancer pathophysiology

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE :